Does Heading in Football Affect Neurological Health?

- HUNG Martha Wing-Hay

- Aug 3, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 11, 2025

Written by HUNG Martha Wing-Hay

Introduction

Due to football’s accessible nature, it is one of the most ubiquitous sports around the world. Heading is a technique unique to football, where the player uses their unprotected head to shoot or pass the ball, very often intercepting the ball at a high velocity of up to 65 km/h (Tierney & Simms, 2018). With the greater awareness of neurological health in recent years, heading becomes an increasingly controversial skill and is often discouraged for young players (England Football, n.d.), with the greatest concern being its plausible damage to developing brains for the youth. Dementia pugilistica, otherwise known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) (Castellani & Perry, 2017), is a neurodegenerative disorder that occurs to athletes involved in contact sports, often involving repeated head trauma. While CTE is most salient in martial arts, such as boxing, it is a great concern in regards to the specific skill of heading in football. This article discusses the biomechanics of heading, the short term and long term physiological impacts of heading for players, and whether or not the research evidence is insofar conclusive to claim that heading causes brain damage.

Biomechanics in football and heading

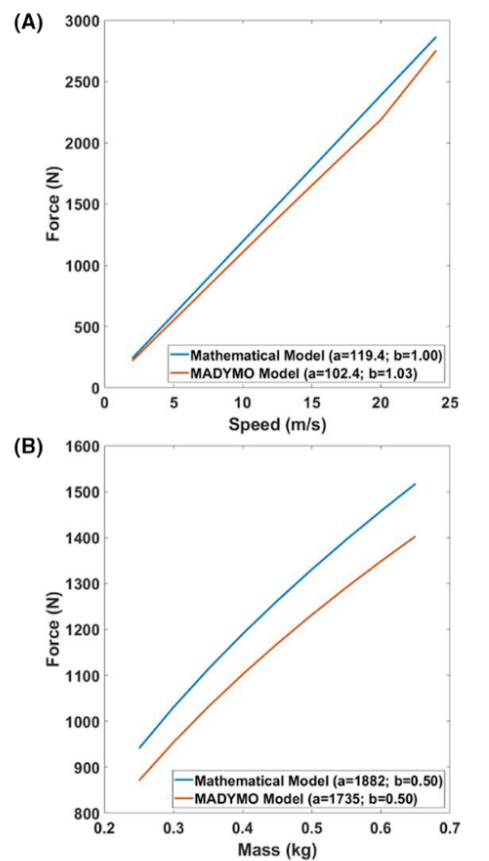

A FIFA-standardised football is manufactured meticulously to maximise the aerodynamics at play, regulating factors such as weight, circumference, internal pressure, rebound and size retention, and is often composed of four basic layers: bladder, fabric, foam and skin, the main purpose of the latter three layers for force dampening to reduce proneness to injury, but also to maintain stiffness for long shots (Tierney et al., 2020). A study conducted by Tierny et al. considered several factors that could cause brain injury, analysing football speed, mass and stiffness, by using a human body model simulation and mathematical model.

The mathematical model is derived from equation

where FHead= peak force experienced by the head;

v = velocity of football at impact of the head;

m = mass of football; and

k = stiffness of football,

where the v, m and k are variables to determine the impact it has on FHead.

The MADYMO multibody human body model, on the other hand, divides the body into 52 different parts based on kinematic joints, to predict rotations, head impact duration, horizontal head translations, head impact velocity and even forces on the neck and head accelerations. Although this is a model originally dedicated to study road accidents and pedestrian impact, a study conducted by the University of Dublin suggested that it is a suitable model to assess physical impact on contact sport, which is now used in rugby and football (Tierney & Simms, 2018).

Results

From the three different graphs, it is evident that speed is almost directly proportional to the peak force of the head, whereas the variables of mass and stiffness only have a near-linear relationship with the force impact on head. Since the velocity of the ball is directly influenced by the force of the kick, this is the factor that weighs the most heavily on the peak force impact on the head, rather than the mass or stiffness.

Short term physiological impact

A concussion is defined as a mild traumatic brain injury that affects neurological function, often experienced with short term symptoms such as headaches and difficulty in concentration, sleep, memory and balance (Mayo Clinic, 2024). A study has shown that concussion rates are higher in football than other contact sports, and up to 22% of football injuries are concussions (Levy et al., 2012). Despite the prevalence of concussions, the findings of short term or immediate physiological impact remains contradictory, where some findings stated that there is no clear evidence of an association between heading and cognitive impairment, while other studies claimed that short-term heading exposure caused over half (54%) of the concussions during a game. Downs and Abwender tested the cognition of university and professional swimmers and football players by an assessment on their motor speed, concentration, conceptual thinking, reaction time and attention, and found that swimmers score higher in every criteria than football players, especially the older subgroup of professional football players, but the test scores amongst the football players did not vary as a result of their history of concussions. Thus, the subconcussive head impacts are more significant to consider, they are the head traumas that do not cause immediate symptoms but the repetition of such concussions over a long period of time may cause neurological disorders or degeneracy.

Long term physiological impact

By neuroimaging, a brain assessment by CT scans and MRIs (Johns Hopkins Medicine, n.d.), studies have found that one third of former professional football players had slight to moderate central atrophy with lateral ventricles of increased widths compared to the control group. Another study concluded that from the MRI scans of amateur football players, the diffusional movement tends to be high in regions of high cellular organisation, such as the temporo-occipital white matter, which negatively impacted their memory. A study by Koerte et al. demonstrated cortical thinning with increasing age in the right parietal, temporal and occipital cortex compared to controls, which is associated with poor visual search and psychomotor speed.

Results from retrospective research

A retrospective study conducted by Mackay et al. among retired Scottish players concluded that most professional football players live a longer and healthier life than the general population, their enhanced cardiovascular system reduces risks of lung cancer and ischemia heart disease. However, they were approximately 3.5 times more prone to fatal neurodegenerative diseases, such as motor neuron disease (4.3 times) and Alzheimer’s disease (5.1 times). Although there is a clear correlation between elite-level football players and prevention of chronic diseases, including dementia, dementia medications were prescribed more frequently to former elite players than the control group of the general population.

This is a useful study to determine the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases amongst professional players, which can be concluded that they do indeed have a greater risk of dementia pugilistica. However, it is important to note two things - one, that correlation is not equivalent to causation, and two, this is not an isolated study on the effect of the skill of heading itself, rather, it is a study based on all the combined effects of professional football training over the years. Thus, to conclude that heading in football affects neurological activity would be an extrapolation, although it does provide insight to the plausible damage of football to the cranial system.

Conclusion

From the analysis of the biomechanics of heading, the speed of the football where a player performs a heading to intercept is the factor that impacts the brain the most. The force impact on the head in turn determines the severity of a concussion, a great risk to football players compared to other contact sports. However, the short term impacts of such concussions are relatively inconclusive. In the long term, the subconcussive impacts are evident in most research findings, such as a reduced cognition and memory, and from retrospective studies, that neurodegenerative disorders are more prevalent amongst professional football players than the general population.

To answer the question, does heading in football affect neurological health? The short term impact is still rather contradictory, while the long term impact suggests that heading has a positive correlation with neurological disorders. It is important to note that these research papers were conducted mostly on professional or high exposure amateur players, and more investigations are needed to allow extrapolation to lower exposure players.

References

Baroof, G. S. (1998, April). Is Heading a Soccer Ball Injurious to Brain Function? Is Heading a Soccer Ball Injurious to Brain Function? Retrieved March 1, 2025, from https://journals.lww.com/headtraumarehab/abstract/1998/04000/Is_Heading_a_Soccer_Ball_Injurious_to_Brain.7.aspx

England Football. (n.d.). Heading Guidance. The website for the English football association, the Emirates FA Cup and the England football team. Retrieved February 15, 2025, from https://www.thefa.com

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Neuroimaging Scan Services at Johns Hopkins All Children's. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved March 1, 2025, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/all-childrens-hospital/services/radiology/diagnostic-imaging/neuroimaging

Levy, M. L., Kasabeh, A. S., Baird, L. C., Amene, C., Skeen, J., & Marshall, L. (2012, November). Concussions in Soccer: A Current Understanding. Concussions in Soccer: A Current Understanding. Retrieved March 1, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1878875011013064?via%3Dihub

Mackay, D. F., Russell, E. R., Stewart, K., MacLean, J. A., Pell, J. P., & Stewart, W. (2019, October 19). Neurodegenerative Disease Mortality among Former Professional Soccer Players. Neurodegenerative Disease Mortality among Former Professional Soccer Players. Retrieved March 1, 2025, from https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1908483

Mayo Clinic. (2024, January 12). Concussion - Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 1, 2025, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/concussion/symptoms-causes/syc-20355594

Rodrigues, A. C., Lasmar, R. P., & Caramelli, P. (2016, March 21). Effects of Soccer Heading on Brain Structure and Function. Effects of Soccer Heading on Brain Structure and Function. Retrieved March 1, 2025, from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2016.00038/full?_ga=2.256539267.929763128.1653451270-611457000.1653451270

Tierney, G., & Simms, C. K. (2018, September). A Biomechanical Assessment of Direct and Inertial Head Loading in Rugby Union. A Biomechanical Assessment of Direct and Inertial Head Loading in Rugby Union. Retrieved March 1, 2025, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343307050_A_Biomechanical_Assessment_of_Direct_and_Inertial_Head_Loading_in_Rugby_Union

Tierney, G. J., Power, J., & Simms, C. (2020, August 24). Force experienced by the head during heading is influenced more by speed than the mechanical properties of the football. Force experienced by the head during heading is influenced more by speed than the mechanical properties of the football. Retrieved February 15, 2025, from https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/165464/7/Scandinavian%20Med%20Sci%20Sports%20-%202020%20-%20Tierney%20-%20Force%20experienced%20by%20the%20head%20during%20heading%20is%20influenced%20more%20by%20speed.pdf

.png)

Comments